The Root of the Problem: A Guide to Solving Weedy Streets

The council has a duty under the Environmental protection act 1990 to keep clean public highways for which they are responsible.

Councils and communities across the UK are facing a shared frustration: a seemingly endless and escalating battle against weeds on our public highways and pavements. As many councils rightly move to reduce herbicide use in line with the National Action Plan, the problem often appears to get worse, leading to public complaints and operational headaches.

The temptation is to blame the new, sustainable tools for being less effective. But what if the problem isn't the tool, but the surface it's being used on? What if, for years, we have been inadvertently creating the perfect environment for weeds to thrive?

This is not a story of blame, but of diagnosis. By understanding the root cause of the problem, we can find a more effective, more sustainable, and ultimately more collaborative path forward.

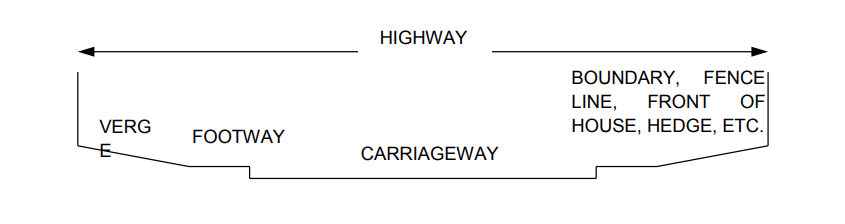

The Highways Act 1980 covers the rights and responsibilities relating to the highway but it is worth defining what is referred to as ‘highway’. The highway is a corridor along which you pass, i.e. it will include verges and footways as well as the road itself and, in general terms, extends from fence line to fence line.

To find a path forward, it’s helpful for both communities and councils to understand the shared legal duty that provides the foundation for our public spaces. The legal framework is clear: Section 89 of the Environmental Protection Act 1990 places a statutory duty on councils to keep highways clear of litter and refuse. The official Code of Practice that accompanies this law is explicit: "refuse" includes "detritus."

This section sets out the legal duty to clear litter and refuse (including dog faeces) from relevant land and relevant highways to which the public has access (with or without payment). Section 89(1) of the Environmental Protection Act 1990 places a duty on certain bodies to ensure that their land (or land for which they are responsible) is, so far as is practicable, kept clear of litter and refuse. Section 89(2) places a further duty on the Secretary of State in respect of motorways and a few other similar public highways, and on local authorities in respect of all other publicly maintainable highways in their area, to ensure that the highway or road is, so far as is practicable, kept clean. Bodies with a duty under this legislation include the appropriate Crown Authority, governing bodies of designated educational institutions, principal litter authorities, the Secretary of State for certain highways, and designated statutory undertakers such as transport companies, train and tram operators, airports and port and harbour authorities. A Code of Practice on Litter and Refuse is issued under section 89 to provide practical guidance on the discharge of this duty.

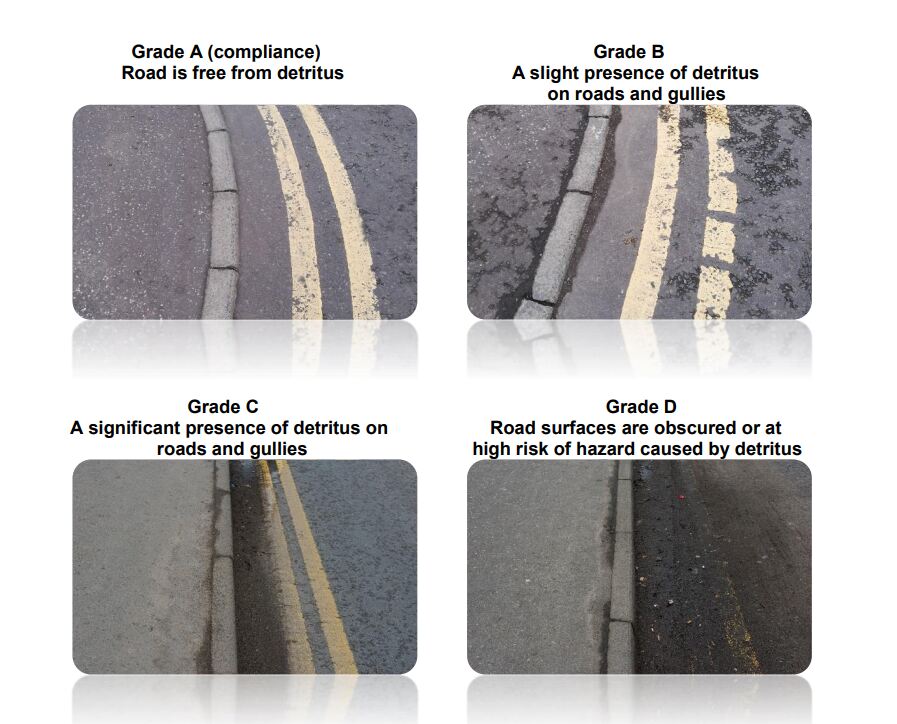

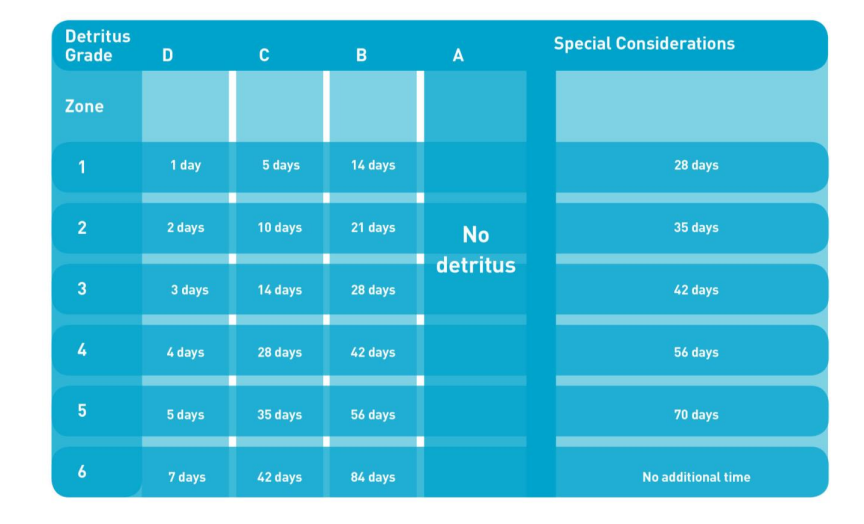

The code of practice makes clear that detritus is a specific part of this duty. Giving a grading system to show the standard (Grade A) and a corresponding table showing the requirements to bring highways back to the standard within a certain time frame.

Response times are the maximum times duty holders have to restore a road to grade A. The response times allocated to grade D are intended to prompt faster remedial action where a potential hazard exists.

Far beyond grade D, most roads I drive down in our urban areas are by now filled with a build up of soil in the gutter and the edges of pavements.

Similar to the road and pavement below in York.

This duty has become a huge challenge. For decades, a reactive "spray-first" model was the accepted, cost-effective standard. However, this has had an unintended, long-term consequence. By focusing only on treating the visible weeds, we have allowed the underlying growing medium—the detritus and soil in our kerblines—to accumulate year after year.

The result is a situation like the one pictured below in York. We are no longer treating weeds growing in the cracks of a clean pavement; we are trying to manage a linear flowerbed that we have inadvertently cultivated ourselves.

Pictures of York. Taken from an article by Steve Galloway.

When a council then tries to use a modern, non-chemical tool on a surface like this, the results are understandably disappointing. It's like trying to fell a forest with a lawnmower. The problem isn't the tool; it's the scale of the task, a problem that began years before with the neglect of the foundational duty to remove detritus.

When Communication Breaks Down: A Tool for Resolution

While proactive partnership is always the best path forward, the Code of Practice itself provides a formal mechanism for when communication breaks down and problems become intractable. It is a powerful legal remedy that is not reserved for officials or lawyers, but is available to every single one of us: The Litter Abatement Order.

What is a Litter Abatement Order?

A Litter Abatement Order is a formal order issued by a magistrates' court that legally compels a council to clean a specific piece of land. It is a tool of last resort, designed to provide clarity and resolution when a council is failing in its statutory duty. It transforms a complaint from a service request that can be ignored into a formal legal process that must be taken seriously.

However, it's probably worth knowing that a Litter Abatement Order exists and how to use one.

Something I was unaware of until very recently.

How to Use the Tool: A 3-Step Guide

Using this tool is a formal process, but it is straightforward.

Step 1: Document the Failure Using Their Own Standards

Your argument should be objective. The Code of Practice provides a clear A-D grading system for detritus.

Action: Take clear, dated photographs of the problem area. Compare them to the official grades to state with authority that the area is at "Grade C" or "Grade D."

Step 2: Send a Formal Written Notice

You must give the council a chance to act. The law requires you to send them a formal written notice of your intent to go to court. This professional, evidence-based approach is often enough to spur them into action.

Action: Write a formal letter or email addressed to the council's Chief Executive or Director of Street Services. Use a template like the one below.

Template for Formal Notice

Subject: Formal Notice of Intent to seek a Litter Abatement Order regarding [Name of Road/Area]

Dear [Name/Title],

This letter serves as a formal notice under Section 7.2 of the Code of Practice for Litter and Refuse.

The highway/land at [Be specific about the location] is currently at Grade D for detritus buildup, in clear breach of your statutory duty under Section 89 of the Environmental Protection Act 1990. Please see the attached dated photographic evidence.

This issue has been previously reported on [dates, if applicable] with no effective action taken.

Please be advised that if the highway/land is not restored to Grade A within 14 days of the date of this letter, I intend to make a formal complaint to the magistrates' court to seek a Litter Abatement Order compelling you to fulfil your statutory duty.

I look forward to your prompt action on this matter.

Sincerely,

[Your Name and Address]

Step 3: Follow Through

If the council ignores your formal notice, you can then proceed with your application to the local magistrates' court. The process is designed to be accessible and does not necessarily require a solicitor for a straightforward case. The threat of this step is often enough.

Here's how they might go about removing the build up with a weed brush (perhaps followed by a road sweeper);

The Real Goal: From Conflict to Collaboration

The Litter Abatement Order is a powerful tool that could be used as a last resort to force action on a neglected area. But it is a stick, not a solution. A one-off clean-up doesn't solve the underlying problem.

The real goal is to collaborate with the council and start a more strategic conversation. We need to move beyond short-term, reactive fixes and to finally confront the need for a long-term, proactive Integrated Weed Management plan.

By proving that inaction has a real legal and financial cost, perhaps we can make the case that a professional, preventative maintenance system; built on the principle of proactive sweeping, is not an expense, but a sound and necessary investment.

It is a tool that allows us, as citizens and experts, to hold our institutions to account and to work with them to build the safer, cleaner, and more respected public spaces we all deserve. I'd be interested to hear from anyone who has given this a try.

If you want to find out more about weed prevention, check our page on Integrated Weed Management for Amenity

No comments yet. Login to start a new discussion Start a new discussion